- Home

- Clair Ni Aonghusa

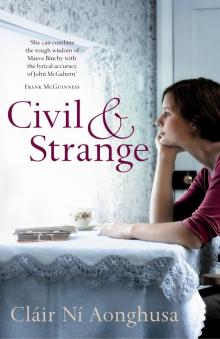

Civil & Strange

Civil & Strange Read online

Civil and Strange

Cláir Ní Aonghusa is an award-winning poet and short-story writer. She lives in Dublin with her husband and two sons. Civil and Strange is her second novel.

Cláir Ní Aonghusa

PENGUIN

IRELAND

PENGUIN IRELAND

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Houghton Mifflin 2008

First published in Penguin Books 2009

Copyright © Cláir Ní Aonghusa, 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright

reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior

written permission of both the copyright owner and

the above publisher of this book

ISBN: 978-0-14-193137-1

For Aengus and Cormac

One

AFTER MONDAY MORNING MASS, Beatrice Furlong makes her way toward O’Flaherty’s shop. She was never a one for weekday Masses, but now she’s like a machine with an unforgiving program. Routine and regulation are what save her and sustain her through each day.

She’s a tall, slim woman, dressed in jeans, a light jacket, and walking shoes. Her hair is an indeterminate brown, and the fine lines on her skin are beginning to deepen a little. Despite this, she looks younger than she is.

Still cool with dew, the morning feels clammy, and the roofs and windows of the cars parked on the street are misted heavily. Traffic through the village of Ballindoon, which takes workers to their jobs in the surrounding factories and towns, is beginning to taper off.

“A fine start to the day,” James O’Flaherty says when she pays for her paper, bread, and plums. James, a balding, heavy-set man in his late sixties, is barely five eight in height. He has an unsettling habit of running his tongue across the front of his yellowed teeth, then working their edges with a cocktail stick, while talking to his customers. Why he can’t floss in the bathroom before opening his shop is a mystery to her.

“You heard about the Tuohy business, I expect?”

She catches a note of suppressed animation in his voice. “No, what?”

“Hanged himself in the garage yesterday. The wife found him late last night. He’s left her with two young children.” He breaks the cocktail stick and drops it into the bin. “God rest his soul,” he says by way of a pious afterthought.

Her body sends intense shooting pains to the top and base of her skull. More than eighteen months have passed since Beatrice’s son, John, took the farm shotgun out of its locked cupboard, went into the old hay barn, smoked a cigarette, aimed the barrel of the gun at his head, and pulled the trigger. That week he had been on his own on the farm, as Beatrice was staying with one of her married daughters in England. It was days before what was left of his body was found.

“That’s terrible,” she manages to say. “What age… was he?”

“Just shy of forty. He was in here the other day buying stamps.”

It’s cruel to tell her like this, but then James O’Flaherty’s unsubtle curiosity won’t be denied. She remembers him the way he was years ago at dance halls and festival marquees. He got one or two local girls into trouble before he settled down with Mary Ann Ellis from the next parish. After his superficial charm and good humor evaporated, Mary Ann found herself living with a dour, insensitive, and casually cruel man. There were no children. After ten years of this, Mary Ann suddenly cleared out their bank account, packed a few suitcases, left the house, and, it was rumored, absconded with a man to Chicago.

Beatrice puts her groceries into her shopping bag, shoving them in roughly without regard for the ripe plums. “You have your news now. You’re set up for the day, James,” she says in a matter-of-fact way.

“Indeed I am. Indeed I am,” he agrees, with an oily smile.

Outside the shop she steadies herself, raises her shoulders, and hurries out of the village.

That same August afternoon, Ellen Hughes struggles up Ballindoon’s main street in the gusting rain. With gleeful ferocity, a downpour sends streams of water rushing along the sides of the streets and floods the drains.

Ellen’s wet hair is pasted to her scalp. She keeps her head down to shield her face against the weather. Sneakily, the wind whips up her long summer skirt, causing it to billow above her knees like a sail. She uses her arms and hands to clamp down the material and catch the escaping pieces of cloth.

Her lips are dry, a cold sore swelling the center of the upper lip. Since the separation from her husband, she has been plagued by bodily eruptions, mouth ulcers, pimples on her nose and chin, and the cold sores that keep her company on a regular basis. “Viruses,” her doctor in Dublin said. “They can erupt when a person is under stress or run down. Keep the lips moist.”

She turns down a lane and makes her way into a walled garden, to a detached house set back from the other houses. As suddenly as it began, the cloudburst ceases and the sun appears. Wet surfaces gleam in the dappled light and water gurgles as the drains clear.

The door lock is stiff and capricious and has defeated her on many occasions, so she knows she must slide the key in at a particular angle and apply a precise pressure to open it. Eventually she hears the click and glide of the mechanism, and she’s almost catapulted into the hallway when the lock yields.

She has known the house since her childhood, when she and her late father visited it. His maternal cousins, a retired teacher, and a nurse, Sarah and Mollie, spent a good part of their lives there. Their youngest sister, Peg, who held no professional qualifications of any kind, never vacated the parental abode even briefly. She left school at the earliest opportunity, worked for years in a local shop, but then gave that up as she was expected to keep house and devote herself to the care of her increasingly infirm mother. Old Mrs. Hamilton — Mam, as they called her — willed the place to the eldest, Sarah, with the stipulation that it would provide a home for each of the sisters during their lifetimes.

The cousins ran the house with military precision. Ellen remembers the smell of polish, the sheen on the kitchen range and the roaring, smoky fire in the living room. She can see bleached net curtains fluttering in a breeze from an open sash window. Every Thursday afternoon the cousins launched an assault on the two downstairs rooms, clearing furniture and books into the hall, brushing and vacuuming the carpets, wiping down skirting boards, bookshelves, and doors, dusting and polishing each piece of fu

rniture before returning it to its original place. In the kitchen, the cooker, fridge, table, chairs, and old-style top-loading washing machine and roller were moved so that the floor could be washed, with food and storage cupboards emptied and cleaned three times annually. In later years, Sarah blamed Mollie for their zeal. She had worked in English hospitals for decades and never shook off a manic enthusiasm for cleanliness.

For much of the year the cousins supplied flowers for the church altar. Ellen can almost see the profusion of flowers, shrubs, and trees in the garden. In the spring and summer months they spent the better part of the day working the garden, obsessively weeding, trimming, feeding, and mulching flowers and shrubs, repositioning plants, digging potatoes, and shaking out onions to dry, their wide-brimmed straw hats bobbing up and down under trees and weaving through tall shrubs and vegetation.

After her father’s sudden death from a heart attack when she was nine, Ellen was afraid that she would never visit Ballindoon again, but her mother, Kitty, continued the tradition of depositing her with the sisters for holidays.

Kitty was never a great driver and, dreading the long, slow journey back to Dublin, she was forever in a hurry. She wouldn’t countenance staying over for a night and always had an excuse for not sitting down to eat the meal the cousins had prepared. Once the cousins had taken charge of Ellen’s case, Kitty would relinquish control, confining herself to a quick pat on her daughter’s shoulder before making her getaway. Admiring her outfit and commenting on changes in her appearance, the cousins would lead Ellen into the kitchen to partake of dinner under their approving eyes.

The trio of sisters were strict in ways, keeping her in each morning to help with clearing up and preparation of dinner for the middle of the day. Then, in the early afternoon, following the washing up, when the last plate had been put away, one of them would say, “The rest of the day is your own,” and off she’d run on her adventures, pausing only to flit back in for tea.

The sudden expanse of freedom was a release for Ellen. She had weeks of running wild through fields on the outskirts of the village, marching up unexplored paths and roads, and the utter delight of skipping down the laneway to the river for a swim, bathing togs wrapped in a towel. On her return from gallivanting, she would call, “Uh-hoo!” like a strident cuckoo, and locate Sarah and the others from their answering trills.

Now the building radiates the intense cold of a place long unlived in and the stench of neglect. Tidemarks of damp stain the wallpaper. Repulsed by perspiring plaster, it is cellotaped here and there in an attempt to hold it in position. The windows are covered in grime, the carpets are filthy, and the floors sag. The upholstery on the chairs is threadbare and stained. Everything is covered in dust.

On her first official visit, following her purchase of the house, Ellen had been met by the fetid odor of rancid grease, damp, and rust in the kitchen. It took her two days to wash down the walls, scour the appliances, and scrub the floor.

Outside, gathering clouds threaten another heavy shower. As she sits in the darkening room her imagination overlays the various odors with the scents she remembers from her childhood.

She has been in the village for the last three days, passing by some of her former haunts, but keeping to herself. She feels invisible, ghostly, and likes the sense of being a mysterious character in a narrative.

A vehicle turns into the driveway. Then the engine cuts out and a door is slammed. Footsteps crunch on the gravel and the doorbell rings. She can’t bring herself to move. The doorbell rings again and a face appears at the window. With a sigh she stands up and goes to open the door.

The stooped figure of a tall man stands before her, his face in shadow, obscured by a cap. A cigarette glows from his lips. “Hiya there, Ellen,” he says.

She stumbles in surprise. “Uncle Matt!” she exclaims.

“It took you long enough to answer,” he carps. “I thought the place was empty.”

“I’ll switch on the light,” she says, and he follows her in. She watches him look around. “Grim, isn’t it?” she says. “I was remembering how Sarah, Mollie, and Peg would sit here in the evenings until twilight and let the room get dark. They’d talk for hours in the shadows, and I’d sit and listen, not opening my mouth for fear they’d remember I was there and send me to bed. They were always very sparing with light.”

He rubs his hands together. “They were sparing with heat, too. Lots of condensation here.”

“It’s the damp and the thick walls. I tried to light a fire in this room but the chimney smokes. We’d be better off in the kitchen. I gave it a good clean-up so it’s just about presentable. Who told you I was about?”

He gives a bark of laughter. “Old Denis Foynes has been trying to place you since you arrived. Terry Fitzgibbon pointed me in this direction, although I half guessed where you’d be. How long are you about?”

“I came last Friday.”

“And is this another of those flying visits?”

She grimaces. “I’m afraid not. I’m staying this time.”

He shakes his head as if in wonderment. “Despite everything I said, you went and bought this wreck.”

She laughs. “I didn’t like any of the new houses. Too big or too cramped, and pretty soulless. I can leave my imprint on this place. When the auctioneer showed me around, I did a lot of sighing over its dreadful condition. The poor man couldn’t believe somebody was finally interested in buying. He was thrilled to offload it.”

“I wonder where the money you paid for this place will end up?”

“Theo Hamilton left everything to a charity.”

“That was the strangest thing out. It’s beyond me why Sarah willed this house to that cousin in America.”

“Old Mrs. Hamilton and Theo kept up a correspondence. She was very fond of him and had some notion that he wanted to retire to Ireland, so she directed Sarah to leave him the place. The will was made before I was born. By the time Sarah died, I was married and had my own setup.”

“Be that as it may, you’ve burned your bridges. It’s a big step, Ellen. What does Kitty make of all this?”

“What she feels is very let down. She’s disgusted that Christy and I have thrown our hats at the marriage. She’s pretty traditional that way. Lie in the bed you made, and all that. She’s given me a good few tongue lashings. In fact, she’s out with me.”

“It’s a cod trying to live your life to please other people. You’re blessed not having children. I know your mother was very taken with Christy but I could never understand his attraction. He was very good at sucking up to her, but he seemed pretty wishy-washy.”

“You never said.”

“It wasn’t my business to tell you who to marry, no more than it’s my place to say that you’re mad to go to the expense of renovating this.”

“I’m sentimental about this house.”

“Exactly. You need your head examined! Anyway, how is the ever-youthful Kitty?”

“Very well. She’s in Italy on a painting trip.”

“Next thing she’ll be moving down here to live with you.”

Ellen laughs. “That wouldn’t be Mum’s style. Actually, she did suggest that we pool our resources to buy an apartment in Dublin. That’s when I first thought of making the move.”

He smiles. “Ballindoon would never be grand enough for that lady. But you’re a different kettle of fish.”

“I like the idea of having a connection with the village. Terry Fitzgibbon recognized me the second time I was in her shop. Apparently, I used to play with her sister.”

He tries the back door. “Is this unlocked?” When she nods, he puts his shoulder to it and pushes it open. He peers out into the garden. “You’ll have your work cut out for you clearing this.” They walk halfway down the overgrown path. “The way the garden falls back behind the house is very attractive. Does it stretch to the river?”

“All the way.”

He views the house from every angle. “It’s not bad real

ly, but it’s a bit cramped.”

“They fed crowds in their day,” she says, “packed us all in, you and Julia, Stephen and Colum, Dad, Mum, and me on our visits. I don’t know how they managed.”

“The miracle of the loaves and fishes.” He follows her indoors as raindrops start to spatter down. “What are your plans? You’re hardly going to live in it the way it is?”

“It needs damp-proofing, rewiring, and replumbing.”

“And bloody central heating. Have you funds?”

“It went very cheap, so yes.”

“After all my trouble driving you about to show you other places,” he grumbles. “And you didn’t tell me your decision.”

“I knew the choice wouldn’t please you, and I felt I’d bothered you enough already.”

He snorts. “My only brother’s only child — my sole connection to Brendan — and you didn’t want to bother me! A courtesy call wouldn’t have killed you.” He stamps the stub of his cigarette into a cracked tile on the kitchen floor. “Who’s going to do the work on the house?”

“I don’t know really. I’ve heard of a builder in the —”

“— I’ll give you a few names. There’s a fellow up the mountains who did work for me. He’s good, very particular.” He winks at her. “Local knowledge is a great thing. You should move fast. You’re living in awful squalor.” He places a carrier bag that contains a bottle on the table. “Brought you a present,” he says.

“What’s that?”

“Open it up and see.”

She unpacks a bottle of whiskey. “You won’t have to be embarrassed if somebody calls. You can offer them a drink,” he says.

“I can take a hint as well as the next woman. Sit down and I’ll pour us a glass each. All I’ve got is water or lemonade.”

“Water is just the ticket.” He looks big in the room, menacing almost, his eyes taking everything in. He can’t settle. He jiggles his knees and taps the table with his fingers. As she rinses and dries glasses, he gets up and prowls about again. “How can you live here?” he asks. He opens the fridge. “Does this thing work?” She nods. He laughs harshly. “Ancient, isn’t it? You might get money for it as an antique.”

Civil & Strange

Civil & Strange